The Newport Tower

Medieval stone tower ... in Rhode Island. Does it look like any other Colonial structure you've seen? Recent carbon dating of the mortar indicates 1400s construction date (see post below).

The Westford Knight Sword

Medieval Battle Sword ... in Westford, Massachusetts. Can anyone deny the pommel, hilt and blade punch-marked into the bedrock?

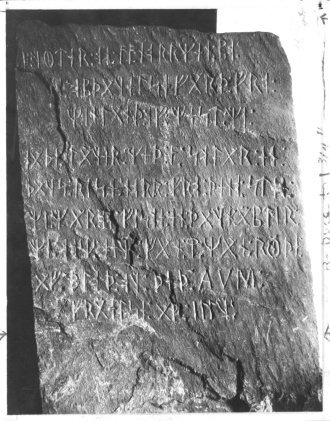

The Spirit Pond Rune Stone

Medieval Inscription ... in Maine, near Popham Beach. Long passed off as a hoax, but how many people know the Runic language? And how is it that some of the Runic characters match rare runes on inscriptions found in Minnesota and Rhode Island? Carbon-dating of floorboards at nearby long house date to 1405.

The Narragansett Rune Stone

Medieval Inscription ... in Rhode Island's Narragansett Bay. This Runic inscription is only visible for twenty minutes a day at low tide--is this also the work of a modern-day, Runic-speaking hoaxster?

The Westford Boat Stone

Medieval Ship Carving ... in Westford, MA. Found near the Westford Knight site. Weathering patterns of carving are consistent with that of 600-year-old artifact. And why would a Colonial trail-marker depict a knorr, a 14th-century ship?

The Kensington Rune Stone

Medieval Inscription... in Minnesota. Forensic geology confirms the carvings predate European settlement of Minnesota--so did Runic-speaking Native Americans carve it?

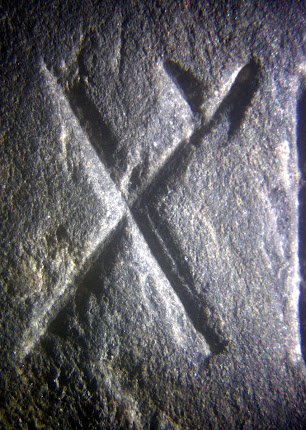

The Hooked X Rune

Medieval Runic Character ... on inscriptions found in Maine, Minnesota and Rhode Island. But this rare rune was only recently found in Europe. This conclusively disproves any hoax theory while also linking these three artifacts together.

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

Tuesday, December 7, 2021

Friday, July 23, 2021

I don’t often weigh in on the Oak Island mystery, though I do regularly watch the Curse of Oak Island show. There are plenty of capable and qualified researchers working on this mystery, and I prefer to focus on less well-known historical enigmas. However, as a Templar historian, I do sometimes uncover things relevant to the Oak Island mystery. I did so recently, something which, unless it somehow turns out to be invalid, ties the Templars to Oak Island with a high level of certainty: coconut fibers.

Coconut fibers have long been associated with the flood tunnels at Oak Island. As the theory goes, the fibers were used to prevent blockage of the box drains in the beach area of Smith’s Cove; these drains fed the flood tunnels, part of the booby-trap system used to protect the treasure buried underground in what has come famously to be known as the Money Pit. Coconuts, of course, are not native to Nova Scotia. And it is absurd to think they had floated up the coast of the Eastern Seaboard, as I have heard one archeologist suggest. Yet there they were.

I stumbled upon a research report compiled by Les MacPhie reporting on samples of the Oak Island coconut fiber having been subjected to carbon-dating by commercial laboratories. (A copy of the online report can be found here: https://www.oakislandtours.ca/.../b09_oak_island_carbon... . The second page of the report is reproduced below.) According to the report, a 1990 test by Beta Analytic yielded a date of 1180 AD, +- 60. A second test in 1996 by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute yielded the remarkably similar date of 1185 AD, +- 35.

These dates jumped out me, being almost an exact match to the 1179 date of a purported Templar voyage to Oak Island (continuing on to the Catskill Mountains of New York) as described in the so-called Cremona Document, first extensively written about in 2017 by historian Zena Halpern. See The Templar Mission to Oak Island and Beyond, by Zena Halpern (CreateSpace 2017). See also The Scrolls of Onteora—The Cremona Document, by Donald A. Ruh (Lulu 2018). According to Halpern, the Templars deposited some or all of their treasure on Oak Island at a place labeled on a map (see below) of the island as “Le Voute en Bas de Terre,” or “The Vault Beneath the Earth” (left arrow). The map itself was labeled “Les Isle des Chene,” or “The Island of Oaks” (right arrow). (Note that this map displays a date of “1347” [not shown], perhaps indicating that it was drawn during a return visit by the Templars, subsequent to their original 1179 arrival.) This map has been regularly featured on the Curse of Oak Island show.

All of the above is available in the public record. What I was not aware of was the fact that coconuts are not native to the Americas. As of the twelfth century, coconuts were grown only in India, eastern Africa, Southeast Asia, and perhaps also Panama, but on the Pacific coast only. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coconut#Origin The Templars, it should be noted, were purported to have traveled extensively to Ethiopia (on the east coast of Africa) in the late twelfth century. See Graham Hancock, The Sign and the Seal (Touchstone 1992), at pages 103-117.

This, to me, was eye-opening. Someone brought the coconut fiber to Oak Island from one of these remote locations. Who, other than the Templars, had the wherewithal to do so in the twelfth century?

For anyone with an open mind, this evidence is difficult to shrug away.

Wednesday, July 7, 2021

My “Romerica” book focuses on dozens of Roman-era artifacts, coins and stone structures scattered around New England and the Ohio River Valley. In the book I speculate that these objects may be related to the Roman Ninth Legion, which mysteriously disappeared from the historical record after helping put down the Bar Kokhba uprising in Jerusalem in 135 AD. Since the book came out last November, I have learned of two new sites which add additional support to the possibility that Roman-era explorers came to America around the second century.

First, a site in the Shenandoah Valley in western Virginia appears to be an ancient iron smelting operation. I recently visited this site, known as the Arkfeld Farm. The owner has done meticulous work documenting his finds and has brought in outside experts to help with testing and dating the site. Here is a picture of what he believes to be part of the remains of the smelting operation:

From the

site, he had three different samples tested at the University of Washington using

Optically Stimulated Luminescence testing. He tested a brick, a mortar/cement

sample, and a piece of slag (a byproduct of iron smelting). The results are as

follows:

Brick Date: 10 AD +-160

Slag Date: 30 BC +-700

Mortar Date: 150 AD +-100

Furthermore,

the owner has documented similarities between this site and an iron smelting

site dating to the Roman era located near Hadrian’s Wall at the England-Scotland

border. In what may be a crucial piece to this puzzle, Hadrian’s Wall was built

and patrolled by the Roman Ninth Legion. (Note that there is no known evidence

of Native American iron smelting operations in North America.)

Second, an inscription along the

shoreline in York Harbor, Maine appears to date back to the Roman era. The inscription,

evidencing considerable aging, consists of two lines of Roman letters.

According to one source, the lettering reflects a version of the Roman alphabet

not used after the 4th century AD. (Images below are 1) photograph

of inscription and 2) “chalked-in” version, both from 1968.)

The script

appears to be an excerpt from Virgil’s Aeneid,

written c. 19 BC, and translates to: “There is far off at sea and facing a storm-beaten

shoreline, a reef often wholly submerged, and pounded by the towering breakers.”

Some commentators suggest the reef in question refers to nearby Boon Island,

where mooring holes 2-3 inches in diameter and 1 foot deep have been found.

Both these

sites appear to add corroboration to the assertions made in “Romerica” that

Roman-era explorers made their way across the Atlantic.

Monday, September 17, 2018

Columbus and the Templars

Saturday, November 25, 2017

Newport Tower Research Updates

Renowned anthropologist and researcher Dr. Gunnar Thompson recently passed away, but before he did he posted to his website ( http://marcopoloinseattle.com ) a number of maps of the

The conclusion that the

Of course, these maps don’t prove that the

My sincere thanks to Black Eagle for his candor and his willingness to help us solve the mystery of who built this amazing Tower.

Wednesday, March 29, 2017

Westford "Stone Sanctum"?

UPDATE 4/24/17: After bringing several Native American tribal elders to view the site, we now believe it may be a "women's circle" where women gathered monthly (they may have waded out in the shallow water to do so). If so, the site would likely predate the late 1600s, after which few Native Americans lived in Westford. The layout--a pathway leading to a circle--may represent the birth canal and womb, with the alter in the center perhaps representing the child. This would be similar to other Goddess fertility sites around the world which also use the "stick and ball" or "balloon" design to symbolize the birth canal and womb.